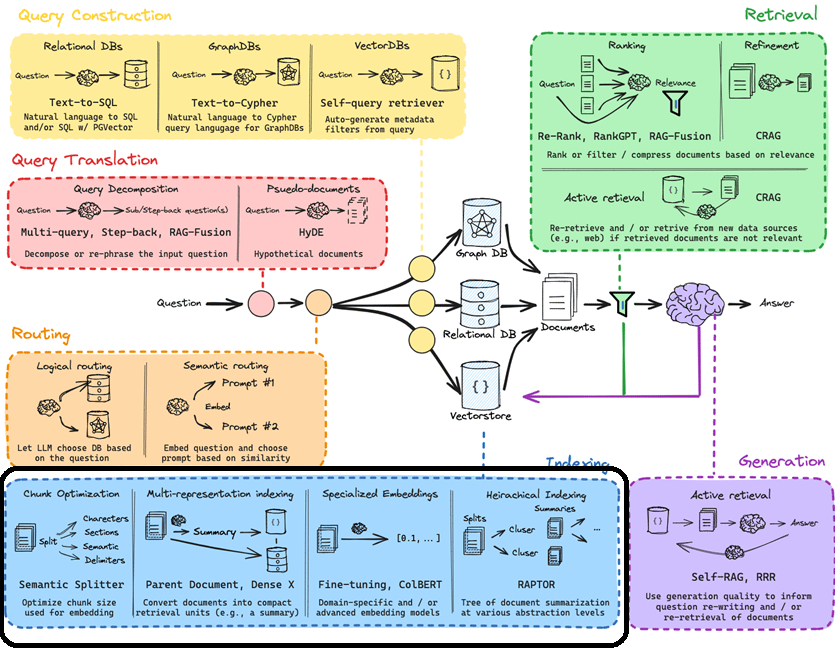

Now that we have done the hard work of translating, routing and constructing the query, how do we make sure the response we get back is not inaccurate, or in a worse case entirely made up ie hallucinated. This is where we now get into setting up the data for retrieval and generation.

Indexing:

We talked about speaking the language of the database when we were doing query construction earlier. Indexing is where we do something similar for the data being queried. There are various ways of doing this, but the end goal is to make it easily understandable for the LLM without losing context. The answer to the question could be anywhere in the document and given the shortcomings of LLMs around real time data, context window and “lost in the middle” problem, it is important to efficiently chunk and then add context to it.

It makes sense to define embeddings at this point, since how we chunk and embed is a core part of indexing to enable accurate retrieval. Put simply, embeddings take a large, complex set of data and convert it into a set of numbers which capture the essence of the data being embedded. This enables the conversion of user query into an embedding (ie a set of numbers) and then retrieving the information based on semantic similarity. How does it look in a multidimensional space? Something like this (note how similar words are closer to each other in this space):

Back to chunking! For easier understanding, let’s assume you are working with a large document, such as an e-book. You may want to ask questions about the content in the book, but since it is too large for the LLM’s context window (and its other limitations), we will like to chunk it up and feed only the portions relevant to the user query to the LLM. But when we do chunk it up, we don’t want the chunk to lose the context of the story or its characters, imagine just picking up a book and starting to read from page 145 – how lost for context will you be? This is where indexing comes in.

Here are a few ways to think about indexing:

1. Chunk Optimization:

The first thing to consider here is the data itself, is it short or long? This will define the chunking strategy and the model to use. For example, if you are embedding a sentence, a sentence transformer may suffice, bur for larger docs, you may need to chunk by tokens, so text-embedding-ada-002 may be the model to rely on.

The second thing to consider is the final use case for these embeddings. Are you creating a Q&A chatbot? A summarization tool? Are you using it as an agentic workflow with the output being fed into another LLM for further processing? If it is the latter, you may want to limit the output to the context length of the next LLM for example.

Source: Medium @thallyscostalat

So, let’s delve into the various strategies:

(i) Rule Based:

Using separators to chunk text, for example space characters, punctuation etc. Here are a few examples of such methods

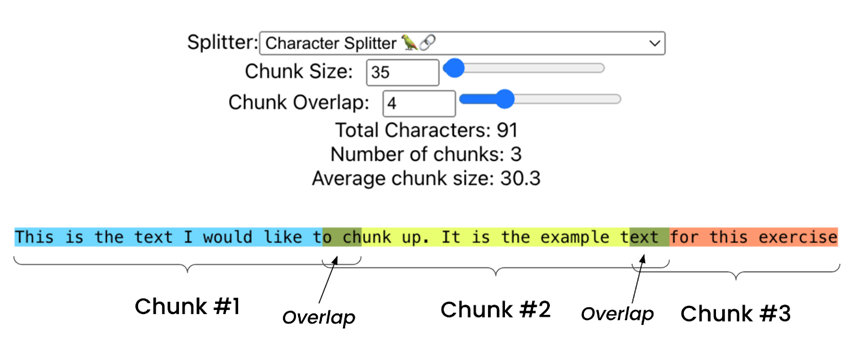

a. Fixed length: The most straightforward way is to chunk based on fixed lengths by counting the number of characters. The mitigant to the risk of losing context by just splitting based on a count, is to have overlapping pieces of text from each chunk, which can be user defined. This is not ideal for obvious reasons, imagine trying to complete a sentence based on the just first half of it. Langchain’s CharacterTextSplitter is a decent way to test this.

Then there are what are called Structure aware splitters ie based on sentence, paragraphs et al.

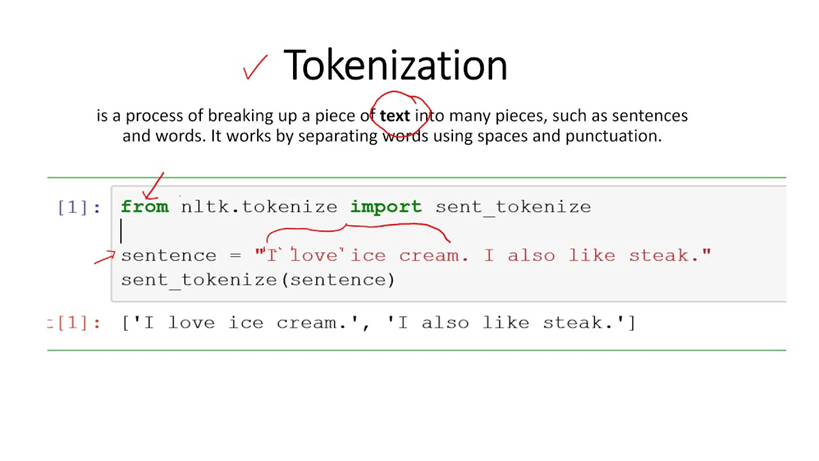

b. NLTK Sentence Tokenizer: This is useful for splitting the given text into sentences. While quite straightforward, it once again has limitations on semantic understanding of underlying text. While great for initial testing, it definitely is not ideal in cases where a context may spawn multiple sentences or paragraphs(which is most of the text we want o query using an LLM).

c. Spacy Sentence Splitter: Another splitter chunking based on sentences and useful when we want to reference smaller chunks. But, suffers from similar disadvantages as NLTK.

(ii) Recursive structure aware splitting:

Combine the Fixed size and Structure aware and we get Recursive structure aware splitting. You will find this extensively used in Langchain docs. The benefit is to be able to control context better. While the chunk sizes may now no more be equal it does help with semantic search, although still not great for structured data.

(iii) Content-Aware Splitting:

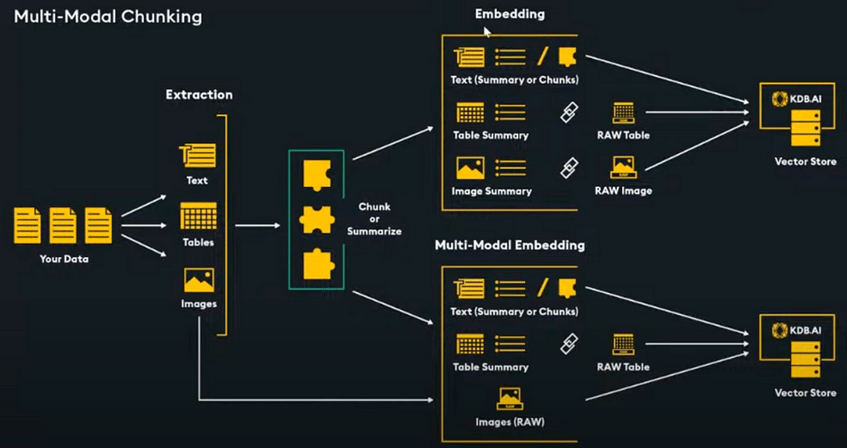

The previous strategies could be good enough for unstructured data, but when it comes to structured data, it is important to split based on the type of structure itself. That is why there are text splitters specifically for Markdown, LaTeX, HTML, pdf with tables, multimodal ie text+images etc).

2. Multi-representation indexing:

Instead of chunking the entire document and retrieving the top-k results based on semantic similarity, what if we could convert the document into compact retrieval units? For example, summary. There are a few ways worth mentioning here:

(i) Parent Document:

In this case, based on the user query, one can retrieve the most related chunk and instead of just passing that chunk to the LLM, pass the parent document that the chunk is a part of. This helps improve the context and hence retrieval. However, what if the parent document is bigger than the context window of the LLM? We can make bigger chunks along with the smaller chunks and pass those instead of the parent to fit the context window.

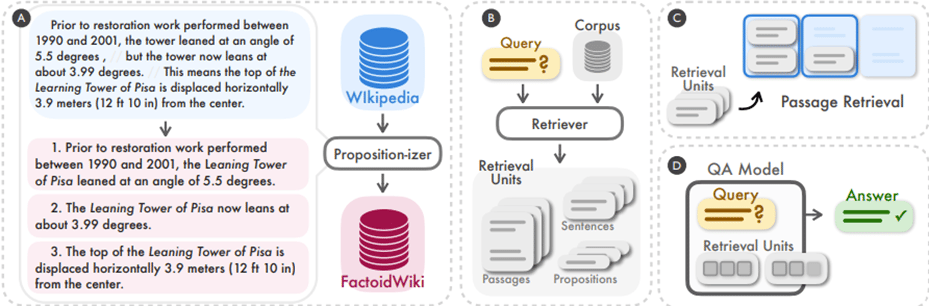

(ii) Dense X Retrieval:

Dense Retrieval is a new method for contextual retrieval whereby the chunks are not sentences or paragraphs as we saw earlier. Rather, the authors in the below paper introduce something called “proposition”. A proposition effectively encapsulates the following:

- Distinct meaning in the text. The meaning should be captured such that putting all propositions together covers the entire text in terms of semantics

- Minimal, ie cannot be further split into smaller propositions

- “contextualized and self contained”, meaning each proposition by itself should include all necessary context from the text.

The results? Proposition-level retrieval outperforms sentence and passage-level retrieval by 35% and 22.5% respectively (significant improvement).

3. Specialized Embeddings:

Domain specific and/or advanced embedding models.

(i) Fine-tuning:

Finetuning an embedding model can be quite useful in improving our RAG pipeline’s ability to retrieve relevant documents. Here, we use the LLM generated queries, the text corpus and the cross reference mapping between the two. This helps the embedding model to understand which corpus to look for. Finetuning embeddings have shown to improve performance anywhere from 5-10%.

Good words of advice here from Jerry Liu on what to keep in mind when finetuning an embedding model:

(ii) ColBERT:

This is a retrieval model which enables scalable BERT-based search over large collections of data (in milliseconds). Fast and accurate retrieval is key here. In case you are wondering, BERT stands for Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers. ColBERT stands for Contextual Late Interaction over BERT.

It encodes each passage into a matrix of token-level embeddings (shown below in blue). When a search is performed, it encodes the user query into another matrix of token-level embeddings (in green below). Then it matches query to passages based on context, using “scalable vector-similarity (MaxSim) operators.”

The late-stage interaction is key here to enable fast and scalable retrieval. While cross-encoders evaluate every possible pair of query and documents, leading to high accuracy, this very feature becomes a bug for large scale apps as computational costs rack up. For quick retrieval from large datasets it becomes efficient to precompute document embeddings, leading to a good compromise between compute and quality.

4. Hierarchical Indexing:

RAPTOR:

The RAPTOR model as proposed by Stanford researchers is based on tree of document summarization at various abstraction levels ie creating a tree by summarizing clusters of text chunks for more accurate retrieval. The text summarization for retrieval augmentation captures a much larger context across different scales encompassing both thematic comprehension and granularity.

The paper claims significant performance gains by using this method of retrieving with recursive summaries. For example, “On question-answering tasks that involve complex, multi-step reasoning, we show state-of-the-art results; for example, by coupling RAPTOR retrieval with the use of GPT-4, we can improve the best performance on the QuALITY benchmark by 20% in absolute accuracy.”

I will take the 20% improvement in accuracy any day!

Vector stores which are used to house these embeddings are increasingly becoming commoditized and hence we shall not spend too much time, except that for larger datasets, it does make sense to use scalable solutions. A few players include Pinecone, Weaviate, Chroma (open source) etc.

Having spent the time and effort in Indexing, we shall now see the fruits of this labour in our next section – Retrieval!